The New York Times reporting on Ranga Dias is emblematic of failed science journalism

Folks, many of you are aware of a major research integrity situation that is developing at the University of Rochester around the claims by Ranga Dias, of room temperature superconductivity. Ranga Dias absolutely observed no such thing. His papers contain unexplainable data artifacts, his reactions are non-transparent in response to data requests and questions about his papers. One of his papers has already been retracted from Nature, and another one is going to be retracted from Physical Review Letters. It is unlikely that this is the end of it, very likely more papers will be found unreliable as it often goes.

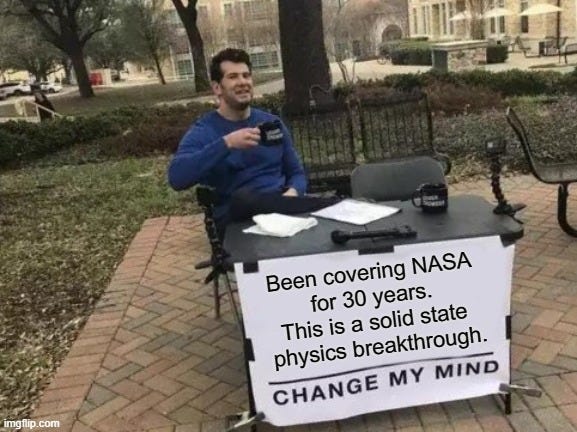

There are excellent comments posted, talks recorded and articles written about this already. Here is an extensive list of materials gathered by Dirk van der Marel, and I am sure there will be more. But one outlet that has been consistently doing a terrible job reporting on this is none other than the New York Times. Its science reporter, Kenneth Chang, took unusual interest in the works of Ranga Dias, having written about him 3 times before with titles like ‘New Room-Temperature Superconductor Offers Tantalizing Possibilities” (here are his other older articles on Dias: 1, 2). Ken mostly covers stories such as NASA launches and telescope discoveries for the paper. But he occasionally dabbles in condensed matter physics. For example, his reporting on the Hendrik Schoen situation from the early 2000’s has been generally well received.

With Ranga Dias’s claims, Ken has been doing a very poor job. After writing about “room temperature superconductivity” enthusiastically, even visiting the lab of Dias to see with his own eyes the amazing work they do, now, after a second retraction has been announced, Ken came out with a new article with a very unfortunate title…

“A Looming Retraction Casts a Shadow Over a Field of Physics”

Now, it is widely known that journalists do not control the titles of their pieces. But the title is symptomatic of Ken’s approach to this reporting, and of broader issues in science journalism and of how it interacts with practicing scientists.

First, what the title directly means is that a field of physics, presumably the study of superconductivity or perhaps the entire wide area known as condensed matter or solid state physics, has suffered a significant reputational hit, because of this newly announced retraction, a second one and not of the most important paper of Dias. (It indirectly implies that the first retraction, arguably a lot more impactful, has done no such harm to physics.)

I am on record as a critic of the research methods used in this field, and I do believe that this topic, as well as the entire scientific enterprise, have major problems related specifically to the reliability and verifiability of major claims. But I have to say that in the case of Dias’s work, the community has done a great job being skeptical, or openly critical and proactively so, for a long time. Physicists, by and large, have not been fooled by this. Take, for instance, this blog, where hundreds of comments from many physicists are taking apart the second Nature paper of Dias, the one the journal published shortly after the first retraction. And the one that Ken Chang of the New York Times, promoted from the pages of the paper when he went to the lab in Rochester and saw “_something_”…

Of course, a journal like Nature can always find a couple of referees that will pass any paper into print, even Dias himself testified that Nature had no concerns about his data. This is a problem of poor scientific culture at Nature, and this is not unique to Nature but is emblematic of many scientific magazines. But the community saw through Dias’s claims early on, and he has also been criticized at numerous conferences and workshops that took place away from the eyes of the press and the internet.

So what does Ken Chang do? After writing not one, not two, but three (or four?) times about this one group’s dubious research, he concludes that now a shadow has been cast on an entire branch of physics. Whereas, in reality, Ken just can’t let go of this story and when finally backed into a corner and forced to face reality with a second retraction, he pivots to blaming the physics itself. In fact, physics has done a great job on this particular case of misconduct. Physical Review Letters has been forced by external pressure from physicists, including at the Virtual Science Forum on reproducibility in condensed matter physics, to start an investigation and found no other way but to retract this paper. In divergence with their usual practice of resisting any efforts to reproduce their publications.

The unfortunate reality is, any physicist, myself included, would be thrilled to end up mentioned in the New York Times. This could be career-boosting, lead to grants, promotions, invitations to speak at nice places, interest from prospective students. In this sense, people like Ken are kingmakers. Some scientists believe that getting into the New York Times is about achieving something remarkable, like a big real discovery or insight, accumulating so much valuable expertise that you are asked to comment on global events or trends.

In reality, ending up in the New York Times is about a random journalist who happens to work there coming across your item, and without having much expertise in your field, making a decision to feature you in their work. As the example of Ken Chang’s persistent reporting on Ranga Dias’s false discovery demonstrates, there is no meaning or value to it. It is of course similar to getting into Nature, all you need to do is present the right combination of material to the editor and depending on what the editor feels like on that day you could be in.

But does it have to be this way? Surely scientific journalism can play and does in some cases play a major role in explaining, promoting and improving science. Examples of reporting just on the Dias’s story prove this (the New York Times not being one of them, but even Nature did a decent job – though they did not call it a ‘disturbing picture’ when two Delft Majorana papers were retracted from their own journal). As scientists, one thing we can do is to keep journalists in check where they go wrong. We should do the same with scientific editors, they are just people and not demi-gods that make or break careers.

The New York Times should admit their role in promoting charlatans from Rochester, and apologize to their readership. Kenneth Chang should rethink his approach to how he selects and researches his stories. After all, he sits on top of the science journalism pyramid and other science journalists likely take cues from him.